Introduction

“An estimated 362,000 refugees and migrants risked their lives crossing the Mediterranean Sea in 2016, with 181,400 people arriving in Italy and 173,450 in Greece” (UNHCR, 2019). After the start of the war in Syria in 2011, the “refugee crisis” has become a common term: In European member-states the situation was felt as an emergency although Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon have received most of the refugees from Middle East (Hoffmann & Samuk, 2016). Barbulescu (2017) questions the Readmission Deal between the EU and Turkey, which aims to stop the refugee flows from Turkey to Greece, and asks if the European Union can still be a “beacon of human rights” or not. De Genova (2017) underlines lack of solidarity amongst the member-states and harsh bordering practices. Despite bordering practices and deadly journeys, some refugees were able to reach Greece and start a life as the project Face Forward… into my home demonstrates. This is the project we examine in this chapter, and our aim is to shed light on how the cultural heritage and cultural distinctions can be deconstructed and reconstructed via interpretation of artworks by refugees who participated in this project.

Despite scholars’ growing interest in the political, legal, and humanitarian aspects of forced migration, there is a need to conduct further analyses from the field of arts, culture and heritage management. This study, therefore, focusing on Face Forward[1], reveals how migrant agency and intercultural communication are combined at the crossroads between art and forced migration. We are particularly interested in how migrant agency via art works is elaborated in this project, and how positive and negative aspects of the project influence the project outcomes. To this end, we employ a case study approach and analyse Face Forward, which is ‘an interactive art project focussed on the stories of people who have been forced to leave their homelands and are rebuilding their life in Greece.’[2]

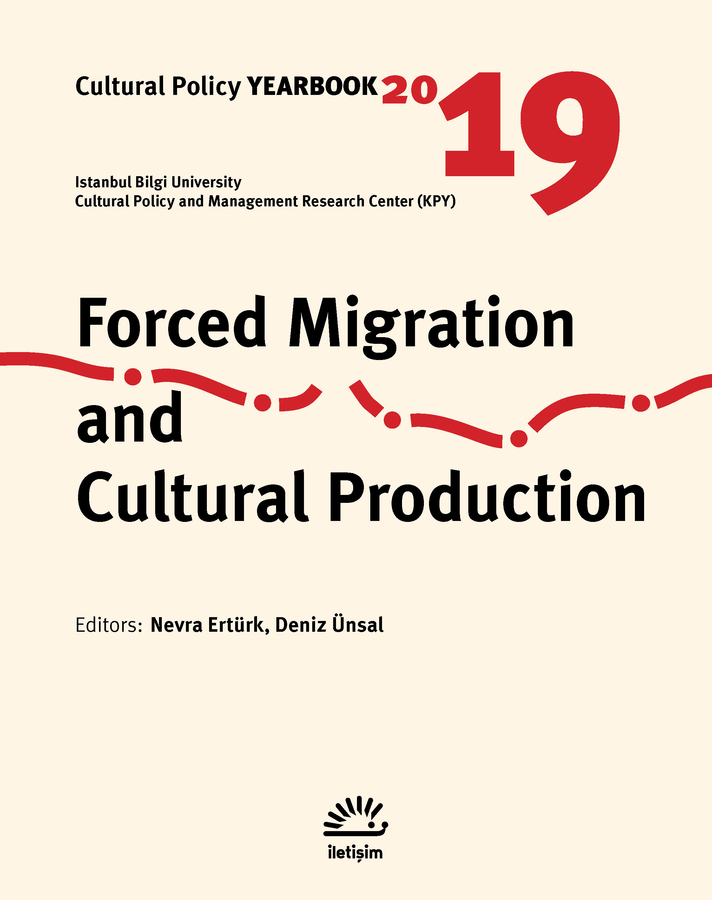

Image 1. Prepared by Derya Acuner, portraits of some of the participants. [3]Photographs are taken from http://www.faceforward.gr/en/faces-stories/

Face Forward centres on the stories of migrants and consists of multiple steps: (i) storytelling workshops; (ii) portrait photo-shoots; and (iii) a photography exhibition about and with refugees and asylum-seekers, who currently live in Greece and benefit from the Emergency Support To Integration and Accommodation programme (ESTIA). It aims to introduce the public to the faces and stories of 26 refugees and asylum-seekers as a thought-provoking stance both by a traveling exhibition and a website where project outcomes are presented. This project manifests a temporality perspective as well as an insider perspective to cultural heritage and migration studies through migrants’ lives. Thus, in this review, we will evaluate how Face Forward focusses on the migrants’ narratives and resistances.

How can we explain and observe resistance in the light of cultural heritage and intercultural communication as we listen to 26 narratives? In other words, how does the project provide space to the migrants’ voices? To be provocative, does this project represent the migrants as the subjects of their own narratives rather than forcing narratives on them? To answer these questions we utilised grounded theory (Charmaz & Belgrave, 2007) when analysing the 26 refugee narratives, examining their past, present, and future through discussion of artworks. Using thematic analysis of the material online and coding migrants’ narratives, five main areas of resistance emerged: family/war-destruction and home country/coexistence and intercultural elements/work, life struggle and future/ gendered resistances.

In this paper, first, we present a brief background for recent migration flows into Greece, where the project is situated. Second, we provide a very brief literature on vulnerability and migrant agency providing our own definition of “resistance”. Third, we analyse the narratives of resistance in five different fields. Finally, the last section evaluates the project’s strengths and weaknesses and our findings on manifestations of resistance in participants’ lives.

Recent Refugee Flows in a Nutshell

Refugee flows from the Middle East, especially from Syria to Jordan, Turkey, Lebanon and EU member states have risen between 2014 and 2017 (UNHCR, 2017). It is not the first time European countries have faced refugee and migrant flows.[4] After the First World War, many European countries had imported migrants and refugees from other countries (Green, 2012). Van Mol and De Valk (2016) separate immigration into Europe in three phases: 1950 to 1974, 1974 to the end of 1980s, and from 1980s to 2012. The first well-known migration is the labour migration into European countries after the Second World War under the guest-worker migration regimes; migrant labourers from Former Yugoslavia, southern European countries such as Italy, Portugal, and Turkey arrived into North-western and continental European countries (Unat, 2002; Morris, 2003). After the 1973 oil crisis, guest-worker schemes came to a halt but immigration continued in the form of family reunification. In this same period, asylum applications as a result of the disintegration of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavian wars were predominant (Van Mol & De Valk, 2016, p. 36). The third period, from 1990s to 2012, asylum applications were mostly from the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Romania, Turkey, Iraq and Afghanistan (Castles et al., 2014). However, the EU migration policies became more restrictive also in this period towards non-EU countries, whilst internal migration within EU gained pace (Van Mol & De Valk, 2016, p. 38).

In the recent decade, “mixed flows” has been used by international organisations, to depict that flows might be including both refugees and migrants. In this study, we focus on refugees as they are the participants of the project and they are refugees of today and migrants of tomorrow[5].

Despite the changing ideological direction today, with anti-immigration tendencies and right-wing extremism, the historical legacy of immigration in Europe has long been a factor shaping European societies in cultural, political, economic, and demographic terms.

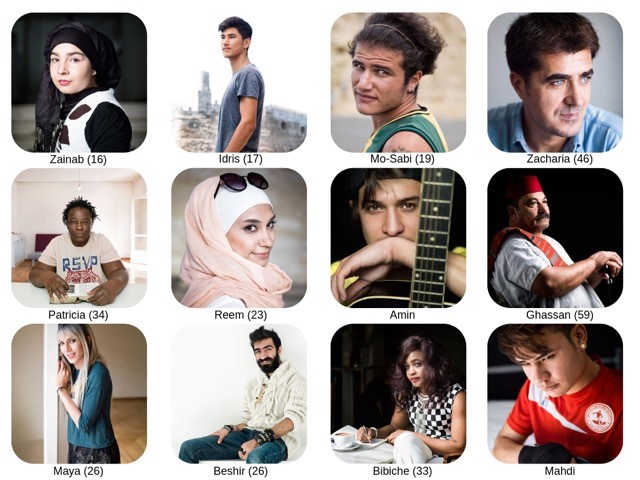

Table 1. Sea and land arrivals in Greece between 2014 and 2017

Source: UNHCR Official Website (based on data from January 2018)

In the face of most recent migration flows, the solidarity among EU member-states has been put into question as France closed its borders, Germany instigated border checks and Hungary set barriers against the settlement and integration of refugees. At the same time, Greece received 32,497 migrants in 2018(see table[6] 1). Considering the recent refugee flows, the three most common refugee nationalities have been Syrian, Afghani and Iraqi (UNHCR 2018). Amongst the participants of Face Forward we observe that there are participants from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq as well.

Depicting Resistance

The dialectic relationship between agency and structure is central to any project dealing with refugees, though especially migrants who have gone through conditions that create vulnerabilities (health problems, discrimination, stigmatization, xenophobia, exclusion from society and services, socioeconomic inequalities, gender perspectives etc.). Vulnerability (of refugees and asylum seekers) is quite a criticised concept as it gained a politically-loaded meaning in the last decade, so much so that it undermines migrant agency. In other words, the institutions that uphold power (INGOs/NGOs [international non-governmental organisations and/or non-governmental organisations]) can determine the definition of vulnerability and apply this concept as a tool of inclusion vs. exclusion. The decision on who is vulnerable is not objective and can evolve into determining migrant (non-)deservingness (Chauvin & Garcés Mascareñas 2014).

Literature has critically examined how migrants are infantilised, stigmatised and marginalised via discourses of vulnerability (Esposito 2017). However, “vulnerability” is not sufficient to understand the negotiations, resistances and survival strategies of migrants, such as migrant women who encounter traumatic experiences in detention centres (Esposito et al. 2019). In contrast with “vulnerability”, migrant agency is alive although in conflict with institutions, politics, policies and experienced INGOs (Ellermann 2010, Bloch et al. 2013, Sigona 2010, Ryan 2018). Resistance strategies of labour migrants (Waite et al. 2015: 481) and undocumented migrants (Ellerman 2010; Schweitzer 2017) reveal the dialectic of integration and non-integration in the host societies. Therefore, vulnerability is not a reason to be non-agentic (Orgocka 2012).

Within the context of migrant agency, we define resistance as such: resisting adverse circumstances via finding new solutions in their new lives, adapting to their environments, creating hopes for the future whilst not forgetting the difficulties and nostalgia for their previous lives and (home) countries. To use resistance in an intercultural context and in relation with art works is necessary to capture the experiences of migrants in the past and their connections with history, daily life, and art in Greece.

Face Forward: Narratives and Their Contents in a Nutshell

Examining the narratives of the refugees involved in this project, we discovered themes related to resistance in different forms: family; war-destruction and home country; coexistence and intercultural elements/work; life struggle and future; gendered resistances. From the participants’ words, a synoptic analysis of these themes is presented in this section.

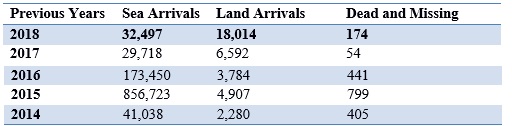

Table 2: 26 stories behind the faces: Summary table for analysis

Family: Some project participants were able to move their families with them, while others could not. Those who could bring their families seem to be truly happy about their children’s prospects.

Farida: I am thinking that my children will grow up in a peaceful environment, they will be able to study and build their future. This thought calms me.

On the other hand, Ali wanted to bring his family with him with considerations of safety and on the condition that he found work:

What worries me the most is that two years have passed since I left Syria and I have not yet managed to do anything for my family, to be able to bring my wife and daughters here. I want to settle somewhere permanently, find a job so that we can all live together in a safe place.

In most of the narratives, the biological family appears in a positive way. Whether the memories are happy or based on losses, the main feelings toward family members are love and wanting to provide care. One clear exception is Maya’s narrative, where she states that her family members had ignored her while she was suffering because of her gender identity back in her home country of Tunisia. Other than her story, some of the younger participants’ narratives demonstrate that even if they love their families, they also put emphasis on their individual independence and existence.

As seen in some examples, “family” does not only refer to the biological families but also people they love in their new lives. Mahdi calls Amin and Hassan his brothers, underlining that “even though they have known each other for five or six months, it feels like they have known each other for years”. Moreover, Bibiche was calling the environment she is in, as family: “And I want to say to all my brothers and sisters here, to the refugees, compatriots and friends—call them what you will, I think of them as family—that we have the chance here to light up the darker places in our mind, the dark memories of the terrible things we have experienced, and to feel human again.”

War-destruction and home country: This theme involves many things such as recovery, transformation and ideas of return. If we contextualise “country”, which is among the most used words, speakers are referring to their home countries, namely the destruction that the war brought, the problems that their society faces and nostalgia for home.

Aboud, who is one of the participants to this project, describes Aleppo realistically and describes the resistance of the people who stayed: “The city is unrecognisable because of the massive destruction it has undergone. You see pictures from today’s Aleppo and you cannot believe that there can be such a place on earth: a destroyed window here, a pot thrown there… However, some people have remained there in the hope that the city will be rebuilt, convinced that all problems are challenges which drive people to work hard and succeed.”

A few of them still urge to return. Amin says: “Last year I did not celebrate Nowruz. I promise you, though, that when I get a residence permit, I will take you all to Iran, set up a tent out in nature and celebrate.” Especially younger participants who are still studying are very idealist, as they want to do something for their “country”. This might also be related to the life course and how they perceive their future. Bibiche says: “I also have a dream like that: I hope one day to work in the European Union as my country’s ambassador and work for peace.”

Coexistence and intercultural elements: Although freedoms and level of tolerance between the east and west are depicted contrastingly, the similarities in referred cultures are found in the examination of the art works created by the participants. These artworks, mostly embedded with intercultural meanings, were “Swedish Flying Carpet”, “Slumber”, and “Bottari”.

Image 2.

Kostis Velonis

Swedish Flying Carpet, 2001

Wood, fringe

8.5 x 80 x 200 cm

Collection of the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens

Donated by the artist, 2002

The wooden carpet by Velonis reminded the participants of carpets made in their countries, and the calmness it brought to their lives. Amin says regarding the carpet: “The Swedish Flying Carpet, by Kostis Velonis, reminded me of the carpets made in Iran and exported to different countries. In Turkey there is a factory that makes carpets like these and exports them to other countries. Most of the workers there are Iranians. These carpets have motifs from nature, flowers and various plants. When you sit on them, you feel calm and peaceful.”

Image 3.

Janine Antoni

Slumber, 1994

Installation

Maple loom, wool yarn, bed, nightgown, blanket, artist’s REM reading on computer paper, REM decoder

Variable dimensions

Collection of the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens

Donated by “The Dakis Joannou Collection”

Zainab refers to her home country Afghanistan and in regard to the artwork of Antoni says: “Janine Antoni’s work with the loom reminded me of Afghanistan, where they still use this device, especially in the villages. People in Afghanistan have practiced the art of the loom for ages. They weave rugs and carpets with flowers and other beautiful designs and lots of beautiful colors. As far as I know, these rugs are very expensive and most of them are sent to abroad. It is mostly women and not men who work the loom, because women know more about colors and designs and they can draw better.” She gives us clues about her own culture (gendered division of labour based on the assumption that women are superior in understanding color and design) in line with the work of Antoni as she also establishes intercultural elements. Moreover, weaving and carpets symbolize traditional artisan work and labour in participants’ home countries and remaking/reworking the future. As Maya says, “we weave our own lives.” When it comes to interculturalism, Bottari’s work is described in different ways: togetherness despite divergences, and difference between feelings inside and outer appearances. Zacharia describes the artwork entitled “Bottari” as “united in diversity”: “The bundle is an object which unites all cultures. In Kurdish we call it bohça. […] Perhaps the artist wanted to talk about the elements and practices that are common to all traditions. Because you can find similarities among people, everywhere. […] the way these bundles placed next to each other illustrates the power of unity as well as the weakness brought about by distance.” Work, life-struggle and future: These themes are mostly related to recovery and continuous struggle in life. Moreover, the participants are convinced that they need to survive and resist adverse conditions; they do not want to forget about their past, but rather focus on the future and on building a new life in a new country. Here are a few examples on how they believe that psychological and cognitive resistance are crucial:

Beshr: “There is a saying, when you fall from a horse you have to get back up again. That is how I am living my life.”

Farida: But now that I am here I have the opportunity to go to school, to learn Greek. That is life, one must work hard and always strive for the best… The greatest difficulty lies in the first step: the first step is the hardest.[7]

Image 4.

Do Ho Suh

Staircase II, 2004

Installation

Translucent nylon

Variable dimensions

Loan from HCO to the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens, within the framework of the Cultural Olympiad

Idris: This work of art has a positive message and shows the truth about life: that you need to put effort into reaching your goals.[8]

Mosabi: It’s not good to stay inactive in our grief, but [we should] pursue our efforts until we reach our goal.

Reem: But hardship makes one stronger. And not only that. Hardship changes a person!

Zacharia: One who fights and does not surrender, shall not die.[9]

Image 5.

Costas Tsoclis

Installation view of the works Harpooned fish, 1985 and Portraits, 1986

Video installation

Color video projections on painted canvases

Collection of the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens

Donated by the artist, 2002 & 2017

Gendered resistances: Gendered mobility and migration patterns are observed (Pessar and Mahler 2003; Green 2012; Uteng and Creswell 2016) in the narratives. For instance, when it comes to jobs and careers, men are believed to be more ambitious than women. Ava says: “My biggest dream, though, is to see my son grow up and become a man who is successful in life.” When she mentions her job prospects though, she seems to be ready to deskill: “I want to find a job in Greece so that I can be creative and do something for my family. I studied mathematics in Teheran with the idea of becoming an engineer. I realize it is difficult for me to work here in this area. But perhaps I could begin with something simple that I like doing and can do well, like being a manicurist. That may be an idea to start out with.”

Bryan says for instance, as he is also a student: “My dream for my future is to study software engineering, but I remember my mother, who wanted me to become a doctor. She insisted on it. She believed it was more important to save human lives than to contribute to the development of technology. That is why I will try to become a doctor. But first I need to see if I am good at school and if I do well in the exams.” However, it cannot be concluded that the females are less idealistic in their career or future prospects, as 26 stories are insufficient to make generalisations.

Most narratives include criticism on gendered beliefs and gendered roles, with an emphasis on gender equality and the importance of equal opportunities. Participants’ narratives show that during the workshops they had fruitful discussions about gender equality in which they criticised the fixed roles and positions of genders. For instance, Amin highlights that “it was the first time for him to take part in discussions on various topics such as the position of women in society”.

While criticising societal tendencies, some participants also shared their personal experiences. For instance, Mo-Sabi states that he does not like the fact that men with earrings and long hair are not accepted in his home country of Iraq, as he wants to be free to physically express himself. Reem shares her experience as a woman with a hijab in Greece, while Maya tells the difficulties she confronted being transgender in her home country of Tunisia.

Concluding Remarks

In this paper we analysed the stories of the refugees, inspired by and based on the chosen artworks in the Face Forward project. Examining the narratives of the refugees and how they interpret the artworks, we observed that they reflect on the past (their country is still a very important aspect of their lives), consider the present conditions (dialectic of suffering from past events and healing) and dream about the future (careers, further mobilities, hopes for their families and countries) with their agency, experience, and resistance via intercultural elements. In our review, we argue that Face Forward respects migrant agency and brings their experiences to the forefront without overly emphasising their vulnerabilities.

First of all, we argue that there are some negative points that can be improved for the next projects similar to Face Forward. The first point is that the matter of sustainability is not described well in the project. For instance, the migrants go through these storytelling and photo sessions, but how do they then continue to make these trainings and sharing(s) a part of their lives? How can the effects of this project be long-lasting for refugees?

Second, we have realised that some of the participants’ stories seem to reproduce the East and West division in regard to politics, and society when it comes to individual freedoms, the tolerance, and living together. The narratives seem to overstate an ancient culture and civilisation that was also theirs but was destroyed by war. Contextualizing East, for instance, Afghanistan, Iran and Syria are depicted as lacking freedoms for women, for LGBTIQ+ [lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer], political freedoms and impacts of religion etc. This might lead to a one sided-view lacking contextualization of the countries and pre-war political dilemmas, and overlook the crucial historical effects.

The narratives connected with the art works deconstruct the Eastern and Western differentiation, and the participants express intercultural elements of coexistence and cooperation when they interpret them. Therefore, the project’s key to success is rooted in these workshops where art works are given intercultural meanings by the participants.

Another success of the project is that the stories of the migrants are not stolen from them. They are at the forefront, migrant agency is central, and their portraits are represented together with their narratives. This presentation allows the reader to familiarise with the problems they have experienced and their future projections as protagonists of their lives. In this sense, the activities have kept the interpreters of art works as central actors of resistance. In addition, an obvious sign proving that their agency was sincerely taken as the core of the project is that stories and portraits of participants have been located under the “Artwork” section of the website with the selected contemporary artworks from the EMST [National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens] collection.

The selection of participants –even though there is no information about the selection process on the website- forms another positive side of the project. Participants compose a diverse and relatively inclusive group in terms of age, gender and sexual orientation, religion, ethnicity, and educational background. This diversity can be enriching for the exchange of discussions within the group and representativeness.

The activities may have been empowering for the migrants, as they were able to express themselves via photos and stories whilst their narratives were translated into other languages (Arabic, Greek and English). The self-transformation through artwork is observed in their narratives (in addition to intercultural elements that help them make links between past and future homes). Discussing diverse aspects of their resistances being inspired by the artworks whilst hearing others’ feelings, thoughts, experiences and dreams, render this project precious whatever the other negative sides might be. In today’s cultural scene, where the democratisation of art and museums as well as the accessibility and active participation in culture and arts are major issues on the agenda, Face Forward provides a case of a good practice in line with such theoretical discussions.

References

Abadan-Unat, N. (2002). Bitmeyen göç: konuk işçilikten ulus-ötesi yurttaşlıǧa (Vol. 1). İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları.

Barbulescu, R. (2017). Still a beacon of human rights? Considerations on the EU response to the refugee crisis in the Mediterranean. Mediterranean Politics, 22(2), 301-308.

Bloch, A., Sigona, N., & Zetter, R. (2013). Migration routes and strategies of young undocumented migrants in England: A qualitative perspective. In Irregular Migrants (pp. 26-42). Routledge.

Castles, S., Booth, H. & Miller, M.J. (2014). The age of migration: International population movements in the modern world. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Charmaz, K., & Belgrave, L. L. (2007). Grounded theory. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology.

Chauvin, S., & Garcés‐Mascareñas, B. (2014). Becoming less illegal: Deservingness frames and undocumented migrant incorporation. Sociology Compass, 8(4), 422-432.

De Genova, N. (Ed.). (2017). The borders of" Europe": autonomy of migration, tactics of bordering. Duke University Press.

Ellermann, A. (2010). Undocumented migrants and resistance in the liberal state. Politics & Society, 38(3), 408-429.

Esposito, F. (2017) Practicing ethnography in migration-related detention centers: A reflexive account. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 45(1), 57-69.

Esposito, F., Ornelas, J., Scirocchi, S., & Arcidiacono, C. (2019). Voices from the inside: Lived experiences of women confined in a detention center. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 44(2), 403-431.

Europe Situation. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/europe-emergency.html on 28th of May 2019.

Face Forward into My Home webpages. Retrieved from http://www.faceforward.gr/en/face-forward-into-my-home/ on 5th of January 2019.

Geneva Convention. (1951). Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. Retrieved from https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b36d2.html on 28th of May 2019.

Green, N. (2012) Changing paradigms in migration studies: From men to women to gender. Gender and History, 24(3), 782-798.

Hoffmann, S., & Samuk, S. (2016). Turkish immigration politics and the Syrian refugee crisis. German Institute for International and Security Affairs

IOM UN (International Organisation for Migration – United Nations). (2019). Definition of migrant. Retrieved from https://www.iom.int/key-migration-terms on 28th of May 2019.

Morris, L. (2003). Managing contradiction: Civic stratification and migrants’ rights. International Migration Review, 37(1), 74-100.

Orgocka, A. (2012). Vulnerable yet agentic: Independent child migrants and opportunity structures. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2012(136), 1-11.

Pessar, P. R., & Mahler, S. J. (2003). Transnational migration: Bringing gender in. International Migration Review, 37(3), 812-846.

Ryan, L. (2018). Differentiated embedding: Polish migrants in London negotiating belonging over time. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(2), 233-251.

Schweitzer, R. (2017). Integration against the state: Irregular migrants’ agency between deportation and regularisation in the United Kingdom. Politics, 37(3), 317-331.

Sigona, N. (2012). ‘I have too much baggage’: The impacts of legal status on the social worlds of irregular migrants. Social Anthropology, 20(1), 50-65.

UNHCR (2017) Global Trends Forced Displacement 2017. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/5b27be547.pdf

Uteng, T. P., & Cresswell, T. (2016). Gendered mobilities: Towards an holistic understanding. In Gendered mobilities (pp. 15-26). Routledge.

Van Mol, C., & De Valk, H. (2016). Migration and immigrants in Europe: A historical and demographic perspective. In Integration processes and policies in Europe (pp. 31-55). Springer, Cham.

References of the Visuals

Image 1. Author’s collage from photos. (2019). Photos retreived from http://www.faceforward.gr/en/faces-stories/ Image 2. One of the selected artworks for Face Forward: Swedish Flying Carpet (2001) by Kostis Velonis Image 3. One of the selected artworks for Face Forward: Slumber (1994) by Janine Antoni Image 4. One of the selected artworks for Face Forward: Staircase II (2004) by Do-Ho Suh Image 5. One of the selected artworks for Face Forward: Portraits (1986) by Costas Tsoclis

[1] From this page on, the project is shortened as Face Forward.

[2] Face Forward … into my Home. http://www.faceforward.gr/en/faces-stories/ [accessed on 28th of May 2019]. In this context, we stick to the definition of refugees according to the 1951 Geneva Convention as the participants of the project fit to the definition of ‘refugees’.

[3] For photographs, see http://www.faceforward.gr/en/faces-stories/ [accessed on 28th of May 2019].

[4] Hereby, we define migrant and refugee differently. Refugee definition is the one adopted in the Geneva Convention (p. 3): “A refugee, according to the Convention, is someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.” Migrant is defined as such (IOM 2019): “IOM defines a migrant as any person who is moving or has moved across an international border or within a State away from his/her habitual place of residence, regardless of (1) the person’s legal status; (2) whether the movement is voluntary or involuntary; (3) what the causes for the movement are; or (4) what the length of the stay is. IOM concerns itself with migrants and migration‐related issues and, in agreement with relevant States, with migrants who are in need of international migration services.”

[5] Recently the term “immigrant” is considered as moving somewhere and staying there, whilst “migrant” implies more mobility and freedom to move. However, this is an ongoing debate.

[6]Greece situation. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean/location/5179[accessed on 28th of May 2019].

[7]With reference to the artwork Staircase II, 2004.

[8] With reference to the artwork Staircase II, 2004.

[9] With reference to the artwork Portraits, 1986.