Brooklyn Museum’s recent exhibition, “Syria, Then and Now: Stories from Refugees a Century Apart”, which took place between October 13, 2018 and January 13, 2019, recounted the changing stories of refugees in Syria over time and placed their differing experiences, a century apart, in a global context. Examining connections between the historical and present-day plights of refugees, it displayed medieval Syrian ceramics from a historic collection alongside artworks by three contemporary Arab artists. The featured medieval Islamic ceramics were originally discovered in Raqqa by Circassian refugees, an ethnic Muslim group that fled Russia around the turn of the 20th century. The exhibition was created as part of the New York Arab Art and Education Initiative, which launched its public programs during the week of October 13-23, 2018. This paper will elaborate on the formation of this exhibit, the artists involved, its display methods, museum programming, as well as the opening events, which were affected by the murder of the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

When I started working at the Brooklyn Museum as a curator of Islamic Art, I recognized an interesting group of ceramics in the collection. These were not the typical kind of beautifully glazed ceramics recognizable worldwide as Raqqa ware with turquoise or copper colored lustered glazes. Instead, their enamels showed weathering almost to the point of obliteration, some vessels had holes in them, and others had slumping shapes. Despite these obvious imperfections, they were acquired by the museum in the early 20th century. I was already familiar with the interesting discovery of Raqqa ceramics from my earlier research (Yoltar-Yıldırım, 2005 and Yoltar-Yıldırım, 2013). Thus, I was quite intrigued by the existence of this group, which included wasters (ceramic products damaged during the firing process and mostly discarded near the kilns). They were acquired by the Brooklyn Museum as early as 1906 and 1908. Some of them were purchased with the museum collection fund from a dealer named Azeez Khayat in New York, whereas others were gifts from Colonel Robert B. Woodward, a significant early donor of the museum, who purchased them from Azeez Khayat as well. Their obvious imperfect shapes and the weathered look of their glazes were not seen as impediments to their acquisition.

Through the years, other well-known collectors such as Mr. and Mrs. Frederic B. Pratt, Mary T. Cockcroft, and Mrs. Horace O. Havemeyer also donated Raqqa ceramics to the museum. These seemed to be in better shape although there were visible cracks with possible restorations.

Almost a year before the launch of the exhibition, I proposed to display the Raqqa ceramics of the museum by highlighting their intriguing but little-known discovery story as part of the permanent gallery of Arts of the Islamic World at the museum. Some months later on April 28, 2018, I attended a symposium sponsored by the Aga Khan program for Islamic Architecture at Massachusetts Institute of Technology named “Translating Destruction on Contemporary Art & War in the Middle East” and organized by Prof. Nasser Rabat. Art historians and artists were invited to give presentations on the convergence of those two themes. As one of the speakers, the Syrian born artist Issam Kourbaj discussed his works on the subject, including a piece he made as a response to the Raqqa ceramics he saw at the British Museum. He had addressed the war and refugee issues in Syria on a grander scale in his other art works. I was very touched by the images of his installation of miniature size boats with burnt match sticks and assembled in large numbers symbolizing the plight of the refugees in the Mediterranean. I also had the chance to see a small group of these boats displayed at the Rotch Library at MIT during the symposium. He had already exhibited his art works at the British Museum, Victoria and Albert Museum, and more recently at the Penn Museum[1], increasingly drawing attention to the Syrian conflict.

The other artist I heard at the symposium was Ginane Makki Bacho from Lebanon. Bacho explained her own story when she escaped to Paris and New York during the civil war in Lebanon (1975-1990). As an artist, she is very sensitive to the current Syrian refugee crisis, with her recent and widely exhibited works focusing on the brutal effects of war and ISIS (Islamic State in Iraq and Syria) in the region. The idea to combine the discovery story of the Raqqa ceramics by refugees with the art works reflecting the current Syrian refugee crisis was born in my mind after this symposium.

Hoping for the right occasion, I kept correspondence with these two artists and expressed my wish to include their works in an exhibition related to the Raqqa ceramics at the Brooklyn Museum. In the meantime, I presented to the museum my idea to combine contemporary works of those two artists with the Brooklyn Museum’s Raqqa ceramics in one exhibition.[2] It was warmly received and colleagues suggested expanding on the theme of refugees that came to Syria and highlighting the museum’s acquisition history of the Raqqa ceramics as well as looking at other artists focusing on the Syrian refugee issues in the United States. Duly, I broadened my research and gathered more information about Azeez Khayat, the dealer who sold Raqqa ceramics to the museum. As he was a known collector in our museum for Egyptian and Ancient artifacts, there were records of him in the museum files.[3] I also got to know Mohamad Hafez, a Syrian artist based in New Haven who focuses on migration and refugee themes in his artworks. Trained as an architect, his works often incorporate elements of Syrian architectural heritage, shown in miniature scale.

The right moment came when our museum received an invitation in June 2018 to be part of the Arab Arts and Education Initiative in New York City (AAEI) to kick off in October 2018. The initiative was intended to be a yearlong collaboration between New York City and Arab world cultural institutions, seeking to forge greater understanding between the United States and the Arab world. AAEI was produced by the UK-based social enterprise Edge of Arabia, and activated by a prospective coalition of partners, which initially included 2 Bridges Music Arts, Art Jameel, ArtX, Asia Society, Edge of Arabia, Middle East Institute, Misk Art institute, Pioneer works, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, UNESCO, Washington Street Historical Society, and Wework.[4] The initiative was also guided by a commitment to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (17 global goals set forth by the UN and world leaders in 2015 to develop a better world by 2030). The funding for the Brooklyn Museum’s project would be provided by the Misk Art Institute.[5] Already having had the refugee-themed exhibition in my mind involving Raqqa ceramics and contemporary artworks, I proposed it to AAEI as the Brooklyn Museum’s project.

The exhibition would involve Raqqa ceramics from the Museum’s permanent collection and loaned works from contemporary Arab artists focusing on the present-day refugees from Syria. The general message of the exhibition would focus on Syria as a safe place where refugees came and created a life around the turn of the 20th century and its juxtaposition with today’s Syria where Syrians escape from war and terrorism. Although America is generally considered an immigrant nation, today’s atmosphere in the U.S., especially under President Donald Trump, has been dismissive towards immigration from certain Muslim countries and the acceptance of refugees. In addition, the U.S. has been militarily involved in and around Syria. However, the attention of the media has been quite limited and usually indifferent to the suffering of the people in Syria and those trying to escape. I thought creating an exhibition on the theme of refugees would help museum visitors to pay attention to the difficult lives of refugees in general and specifically to the Syrian refugees today. It could raise awareness for that part of the World and generate compassion for the precarious situation of the Syrian refugees. The exhibit would also be in line with Brooklyn Museum’s mission “to create inspiring encounters with art that expand the ways we see ourselves, the world and its possibilities”. In addition, being able to tell different stories about a group of medieval Islamic ceramics from the permanent collection of the museum would be consistent with the museum’s recent efforts to activate its historical collections with new perspectives and stories. Raqqa ceramics are known within Islamic ceramic productions and several museums in the U.S., including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, display them but their discovery story by the Circassian refugees is hardly known or told in museum settings. Similarly, the story of the immigrant Syrian dealer who sold Raqqa ceramics to the Brooklyn Museum in New York was not known or brought up in relation with the Brooklyn Museum collections before. We now had an opportunity to tell several stories related to these ceramics and we could bring a crucial social issue regarding refugees and immigration upfront.

My idea was warmly welcomed by the museum and the AAEI. Having a significant social issue as the focus helped the exhibition to be pushed onto the exhibition calendar despite the lack of time that would be normally needed to prepare an exhibit. Stephen Stapleton, the chief coordinator of the AAEI, also suggested that there could be further collaborations between the museum and another partner of AAEI known as the Washington Street Historical Society, which would focus on Little Syria, the neighborhood in Manhattan that once received Syrian immigrants. This seemed to be a fruitful opportunity to expand the refugee-immigration theme and connect it with New York’s social history.

Although time was tight to start an exhibition in July with an opening in October, there was enough commitment and excitement at the Brooklyn Museum. Director, Anne Pasternak, took initiatives to make the exhibition preparations move quickly: gallery space was created right at the entrance of the museum; international loans were arranged to include the works of two artists living abroad; and public programs involving all three artists were planned for the opening and continuation of the exhibit. Among the 17 sustainable development goals of UNESCO, three of them, namely No Poverty, Zero Hunger, as well as Peace and Justice seemed appropriate to be adopted for the exhibition.[6]

Preparations started with arranging the conservation study of the museum’s Raqqa ceramics which were going to be displayed, the loan of the works including the international ones to arrive on time for the exhibit, and public programs to enhance the message of the exhibition. We also started looking for possible artist engagements with schools in Brooklyn in order to enhance the educational component of our partnership.

The space we would be able to use for the exhibition was a single room of about 1000 square feet (92 square meters) at the entrance of the museum. Part of the display was dedicated to the Raqqa ceramics from our collection. Apart from two exemplary Raqqa objects, one small jar and a partial lustered plate, I wanted to show the ones that were found by the Circassian refugees and brought to the museum as early as 1906 and 1908 and sold by the Syrian dealer before Raqqa ceramics became sought-after collector items. I wanted to explain the reasons behind their weathered look and make up. It would be important to add the results of the conservation studies to complement what we already knew about these objects. Several different methods, such as X-ray and ultraviolet light, would help us to better understand their technical qualities. We decided to incorporate the visual details of this study on a monitor in the exhibition. We also thought of making the display case for the ceramics look distinctive to give the idea of their discovery by refugees who were digging the earth. After checking with the conservators, we settled on a suitable sand for the bottom of the case.

I sought to also highlight the story of the dealer, especially his immigration to New York at the end of the 19th century and his activities in the art world as a dealer. Although many of his activities, such as digging as an amateur archaeologist and selling his finds would not be allowed or found ethical by today’s standards, I decided to explain his life as it is and show how his life as a Syrian immigrant became a success story. He was one of many migrants who came to New York from greater Syria for a better life and work opportunities in the late 19th century. Although not much of it is left today, there are archival photographs of the neighborhood he initially lived, called “Little Syria” in the Library of Congress that we could show as part of the exhibition, perhaps on a monitor. This would make direct links with Syrians and New Yorkers, which was one of my goals of this exhibition. Illustrating the history of Syria had to incorporate different phases: the Abbasid times when Raqqa was established as an important caliphal city in the 8th century, the medieval era when a ceramic industry was established, and the late Ottoman period when Circassians were settled in Syria in the late 19th-early 20th century. This was challenging since our audiences would most likely not know much of the geography or the history of the region. Hence, suitable clear language and some maps seemed necessary.

The present-day refugee crisis in Syria was somewhat easier to tell. Issam Kourbaj and Mohamad Hafez were Syrian and had family and friends caught in the Syrian crisis. One artist, Ginane Makki Bacho, was not Syrian but she escaped a civil war in Lebanon and took a personal interest in the situation of the Syrian refugees especially those arriving in Lebanon. As time was tight, we settled on the artworks that I was already familiar with. Issam Kourbaj would bring his miniature boats symbolizing the refugees trying to cross the Mediterranean waters. He had other installation ideas we appreciated, such as his actual UNCR tent installation incorporating refugee camps made of small boxes, however time and space were not in our favor. Doing live installations with matches was also problematic due to the museum’s fire code among other reasons. The artist could only be in New York for a week during the opening of the exhibition in October. Thus, we decided to use his small boats for the exhibit. The other Syrian artist, Mohamad Hafez, lived in the U.S. and could therefore be engaged in museum activities for a longer period of time. Several of his works were about his homeland and its recent destruction during the civil war that he just barely escaped. Among his works, we chose a large piece in the shape of a framed mirror displaying a protruding Damascus city scene with an audio recording of the city and another three-dimensional work reflecting a bombed building coming out of an open suitcase. Hafez’s pieces were focusing on the architectural heritage of Syria and represented no humans, which diverges from the other two artists who were mainly dealing with the human tragedy.

Ginane Makki Bacho’s recent work was consumed with the impact of the Syrian refugees numbering close to half of Lebanon’s own population. She was also affected by the terrorism of ISIS that she observed in the media. Her works are mainly made from scrap metal, reflecting the harshness of war and its effects. She and I decided to incorporate in the exhibition her refugee series, small size metal boats filled with refugees, and small statue groups waiting to go on board. Although her other works on ISIS related themes were very powerful, I still wanted to bring into focus the refugees rather than the ISIS atrocities.

The approaches, materials, and styles of the three artists were quite different and yet all of them asked the viewer to confront and engage with the Syrian refugees in some aspect. In the labels I wanted the artists’ own voices to be heard, thus they commented on their own work. The word choice for the title of the exhibition was also the result of the two refugee experiences in Syria, one lived by the Circassians that would be reminded by the Raqqa ceramics they discovered and one that is lived now by the Syrians brought to light by the contemporary art works.

In little over two months, the exhibition was ready to open. Below, you will find an explanation of the different elements of the exhibition. Interpretive materials, such as wall texts, labels and maps, were created with this information in hand.

The Discovery of the Raqqa Ceramics by Refugees

The medieval Islamic ceramics displayed in the exhibition were originally discovered around the turn of the 20th century in Raqqa, Syria, by Circassian refugees, an ethnic Muslim group that fled Russia. In the late 19th century, Circassians living in the north central Caucasus who were escaping military conscription, forced religious conversion, and the imposition of the Russian language, were settled by the neighboring Ottoman Empire in the Balkans, Anatolia, and Greater Syria (Chatty, 2017, pp. 54-79; Hamed-Troyansky, 2017). Out of the three hundred families settled in Syria (Ottoman Syria includes present-day Syria, Lebanon, State of Palestine, Israel, and Jordan), about fifty were placed in Raqqa, a minor outpost back then.

Raqqa (meaning swamp in Arabic since it is close to the river Euphrates and its tributary Balikh) was established in Hellenistic times. Under Muslim rule starting in 639 it became a prosperous city, especially during the reign of Harun Al-Rashid, the famous Abbasid caliph who ruled a large empire in the late 8th-early 9th century. The city almost became second to Baghdad during Al-Rashid’s reign (786-809), replete with monumental palace buildings, mosques, baths as well as markets. Although the city lost its significance with the fall of the Abbasids in the 10th century, it had another revival in the late 12th and early 13th century under the Ayyubids (1171-1260). The ceramic (and glass) industry, which goes back to the Abbasid period, prospered during the Ayyubid era. This however ended abruptly when the city was destroyed by the Mongols in 1265. After this demolition, Raqqa never regained prominence for several centuries and many of its monumental buildings slowly fell into decay (Meinecke, 1954-2002). When the Ottoman government settled the Circassians in Raqqa in the late 10th, several of its medieval brick monuments were visible but in a ruinous state (Jenkins-Madina, 2006, p. 12).[7] The refugees were initially given permission to look for bricks in the ruins in order to build houses for themselves. However, this digging activity unearthed not only the medieval masonry of the city but also beautifully glazed ceramics that remained buried under debris since the destruction of the city in 1265. As early as 1899, large ceramic jars and bowls were sold to local dealers who would then sell them at higher prices in Aleppo igniting a digging frenzy afterwards (Yoltar-Yıldırım 2006, pp. 195-201). The dealers soon associated the ceramics with the palace of the Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid, the legendary figure and a central character in the Arabian Nights (Jenkins-Madina 2006, pp. 11-19). This literary classic in Arabic was known to the Western world through 18th century French and 19th century English translations. Harun al-Rashid, Scheherazade, Ali Baba, Aladdin, Sinbad are all characters from this classic novel that continue to attract attention.

The detailed written communication of the local administration in Raqqa with the central administration in Istanbul and the Ottoman Imperial Museum shows that the digging was pervasive and beyond the control of the local administration and gendarmerie. Thus, on several occasions, help and money were requested to deal with the problem. Although the permit to dig for bricks was revoked in December 1900, illegal digging activity continued and the news of the beautiful glazed ceramics coming out of Raqqa began spreading through dealers. Raqqa ceramics were sold in Paris and London as early as 1903.

The Ottoman Imperial Museum in Istanbul began its own excavations in Raqqa in January 1906. According to the finds of the excavation and the description of the excavator Theodor Macridy, the 1906 excavations took place near the kilns where ceramics were originally produced. Therefore, some kiln furniture and numerous wasters or rejects, which were normally thrown away near the original kiln sites, were found and sent to the Imperial Museum in Istanbul. Soon after the 1906 campaign, clandestine excavations continued and a random dig hit the old market street of the city. Dubbed as the “Great Find” by dealers, large unglazed jars used for storage were found with their contents intact (Jenkins-Madina, 2006, p. 16; Yoltar-Yıldırım, 2013, p. 82). These large jars contained beautifully glazed and well-preserved Raqqa ceramics in the identical state that they were to be sold in the market before the city was destroyed by the Mongols. Many of them found their way into European and American collections, and were conveniently associated with the palace of the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid. Prices in the art market increased quickly, especially in 1920’s with this association. Pieces from the “Great Find” can be seen in the Freer and Sackler Museum in Washington, D.C. and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.[8]

After the site was exhausted of its finds, Raqqa ceramics, especially those with turquoise glazes or lustered decoration, became a well-known name within Islamic ceramic production. Later scholarship revealed that they were not produced in the Abbasid period as the dealers wanted to believe, but later in the Ayyubid era when the city experienced a second revival. Strangely though, by the end of the 20th, the Raqqa excavations both legal and illegal were forgotten, and Raqqa came to be questioned as a production center. Many ceramics from that city were forgotten in museum storage or assigned to Iranian centers of production. The group of Raqqa ceramics first acquired by the Brooklyn Museum in 1906 was identified as “Mesopotamian” with the suggestion of being possibly from the pre-Islamic periods. Since the fame of the Raqqa ceramics had not yet reached a wide audience in 1906, it is possible that Azeez Khayat, the dealer who sold them, was perhaps unaware of the Islamic dating or preferred to sell them with a generic Near Eastern appellation.

Raqqa Ceramics in the Exhibition

The exhibition featured 17 ceramics (Fig. 1), and several of them were acquired by the museum in 1906, 1908, and 1909. The conservators and I studied each object and determined that there were three groups.[9] The first group included six intact or original pieces that exemplified the world-renowned Raqqa ceramics: black underglaze painted turquoise type (small vase with black stripes, 36.944) or copper-colored lustered examples (a large plate with a peacock image in the center, 78.81). The group also included a weathered ewer (09.314), two oil lamps (09.307, 09.309) and a glazed sphero-conical container (09.313). The second group consisted of wasters or ceramic products damaged during the firing process and therefore discarded: a slumping ewer (06.3) and a jug with a hole at the bottom (08.24). These were displayed in the case exposing their failing features to the viewers.

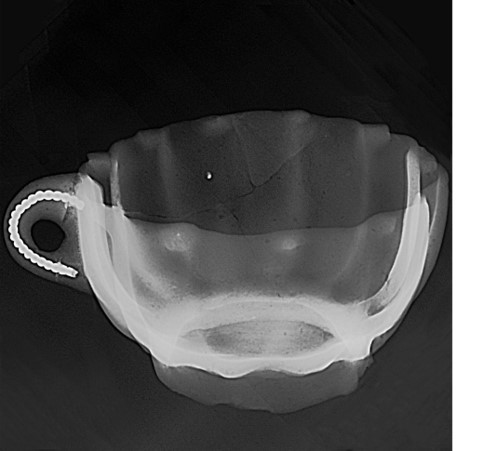

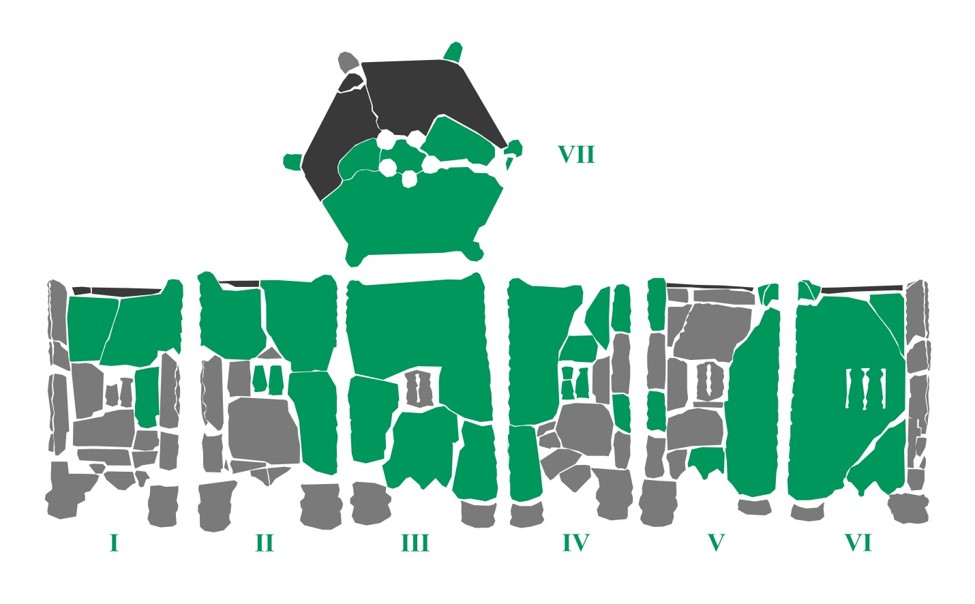

The third group contained nine pastiches, ceramics that were “restored” in the early 20th century by dealers, often with pieces from different objects, including wasters. Three such bowls (08.18, 08.32, 08.35) were simply pieced together from several fragments that may or may not have belonged to the original vessel. X-rays revealed that handles were fabricated with metal wires and fills were added to some pastiches to make the pieces more readily saleable in the art market (08.19, 08.21 (Fig. 2), 08.23). Overpainting and purposeful weathering of the surfaces also made these objects look as if they had been found intact. On a monitor near the case we showed images of two such pastiches, a jug and a lobed cup (08.19 and 08.21) under visible light, ultraviolet light, and X-ray. The added handles with wires in them were clearly visible in the X-ray images. One bowl (08.36) consisted of several fragments, one of which included a chip of a rim from another vessel on its outside. One large vase (42.212.61) with relief decoration was completed almost from a half jar with modern pieces. One small stand (10.15), a characteristic object from Raqqa, was made up of nearly 100 fragments. Before the conservation study of the object for this exhibition, it was thought to be more or less complete, although with a very unevenly preserved glaze. An archival photo taken in 1986 shows the state of the object when it came to the museum (Fig. 3). A diagram (Fig. 4) maps all the previously concealed sherds which made it up. Around one half to two thirds of the object was made from pieces of a single stand, although some of the pieces have been cut down or turned 90 degrees. The remaining fragments came from three or four different stands of similar shape. An X-ray of the top face of the object reveals that a full half of it has been replaced with a ceramic piece featuring a completely different pattern. Once the pieces were fitted together, the gaps were filled in with plaster. The entire object was covered in paint with glass flakes and metal leaf in order to imitate a badly degraded glaze. Even the interior of the object, invisible from the outside, was spackled and painted in order to hide the object’s true nature.[10]

Figure 1. Display of Raqqa Ceramics, photo: Jonathan Dorado

Figure 2. X-ray of 08.11, photo: Harry Debouche

Figure 3. 10.15 Photo: Courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum

Figure 4. 10.15, Diagram by Harry Debauche

Figure 5. Syrian Food Seller. George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

The Dealer Who Sold Raqqa Ceramics in New York

The story of the dealer who sold the Raqqa ceramics to the Brooklyn Museum as early as 1906 turned out to be quite interesting and relevant to the theme of the exhibition. Not a refugee but an immigrant from Ottoman Syria, Azeez Khayat (1875–1943) was born in Tyre (Sur) in Lebanon. At a young age, he came to New York through Ellis Island in 1893 and became a United States citizen five years later. Using the small collection of ancient glass which he brought with him, Khayat managed to attract some collectors and start a life as a dealer in Lower Manhattan, on Rector Street, in the neighborhood known as Little Syria. On repeated trips to his homeland, he was able to bring back many more artifacts -ancient glass, coins, seals, and ceramics, often excavated by his own workmen- and sell them in a gallery he opened first on West Eleventh Street and later at 366 Fifth Avenue, opposite the Waldorf Astoria Hotel. Many notable U.S. museums acquired significant objects through him. Toward the end of his life, after a long and prosperous career in art dealing, Khayat left New York to live in Haifa, where he purchased a large stretch of land on the beach and turned it into a popular resort, known as the Khayat Beach. Two of his daughters continued to run his gallery for several decades in New York (Bergman, 1974).

Little Syria in Manhattan

The neighborhood often referred to as “Little Syria” in the late 19th -early 20th century encompassed Washington Street and the surrounding streets on the Lower West Side of Manhattan (Jacobs, 2015). Like Azeez Khayat, newly arriving Syrians, mostly of Christian faith but also Muslims, lived in this neighborhood (Fig. 5). The St. George Syrian Catholic Church on 103 Washington Street is still standing although it is currently used as a bar. Records show that a masjid financed by the consulate general of the Ottoman government was also in use nearby on 17 Rector Street.[11] The Syrians that lived in “Little Syria” were quite active through publishing newspapers and literary journals in Arabic (Jacobs, 2015, pp. 260-281). As one of them, the famous poet Khalil Gibran (1883-1931) resided in that area.[12] When urban changes in the neighborhood occurred due to the construction of high rises and later the Brooklyn Battery tunnel and the World Trade Center, “Little Syria” completely lost its identity. The Syrian residents moved to New Jersey and Brooklyn. Today, only a few buildings are preserved and the name “Little Syria” vanished, unlike Little Italy or Chinatown, which were neighborhoods established by other immigrant communities.

Photographs of Syria

On August 24, 2018, the New York Times published an article by Andrew R. Chow entitled “Initiative Brings Arab Art to New York Museums” in the Art and Design section of the paper about the upcoming program of AAEI.[13] Mohamad Hafez was featured as one of the artists of the Brooklyn Museum exhibition dedicated to Syrian art. Peter Aaron, a photography artist who worked on Syria, saw the article and contacted me to discuss his work. Although timing and space issues did not allow his actual photographs to be displayed in the exhibition, we agreed on including a video showing a collection of Aaron’s black and white photographs he took in Syria in 2009 before the crisis broke out in 2011.[14] His impressive photographs not only documented the rich architectural heritage of Syria but also its people and life before the crisis. Since then, many of the structures seen in his photographs have been severely damaged or destroyed. The photos on many levels reminded the viewers of the seemingly normalcy of life in Syria before the recent crisis and showed how a place with such a rich culture could turn into a war zone so quickly, converting millions of citizens into refugees. His works aim to remind the visitor that no one and no place is immune to such disasters.

The Main Message of the Exhibition

The civil war in Syria broke out in 2011 following the pro-democracy protests and the president Bashar al-Assad’s brutal force to put them down. Since then, Syria evolved into a country of turmoil that many seek to escape. Raqqa itself became synonymous with the terrorist group ISIS, which until recently proclaimed a new Islamic caliphate from the same town that the eighth-century Abbasid Caliph Harun Al-Rashid once ruled his empire. The ongoing civil war in Syria and the rise of ISIS, amid continuing acts of violence against civilians, forced many to seek refuge outside Syria not only in neighboring countries but also in distant lands in Europe and North America. As these changing tides of history suggest, anyone, anywhere, can become a refugee, and no geographical location can guarantee immunity.

In the exhibition, the present-day plight of Syrian refugees is reflected in the touching artworks of three contemporary Arab artists, representing three generations born, respectively, in the 1940’s, 1960’s, and 1980’s. Each of them tells a different story, but in the end, they all call upon our common humanity for compassionate attention to refugees’ precarious situation worldwide.

Contemporary Artists

Ginane Makki Bacho was born in Beirut, Lebanon in 1947. She holds a BFA from the Lebanese American University in Beirut and an MFA in printmaking and painting from the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York. Since 1983, Ginane Makki Bacho has been working with metal. Her works in the exhibition are entitled Refugees Series and consist of three large bronze boats packed with figures and several groups of steel figures including men, women, and children waiting in line with suitcases in their hands. She describes her work in the exhibition as such:

“I have always dreamed of peace, freedom, and happiness. However, in real life we are surrounded by hatred, injustice, and continuous deprivation of the most basic of human rights. When the civil war broke out in 1975 in Lebanon my family’s journey of survival started, fleeing from one place to another, seeking refuge first in France then the United States. My art revolves around my experiences through the various traumatic wars I witnessed not only in Lebanon but in the region since then. I immersed myself in a cathartic task by depicting the disasters I witnessed. After years of watching the war in Syria and the spread and horrors of ISIS through the media, I threw myself into reenacting the exodus of the thousands of people attempting to escape and find sanctuary elsewhere, to spare their families from imminent death. Sadly, many of them drowned or were lost at sea. These spectacles that the media was covering were something I had witnessed early in my life during the Lebanese civil war, but the Syrian refugee crisis is on a totally different scale. In my work, I use scrap metal to emphasize the degradation of civilization we currently live in. The use of rough metal conveys the misery of the people with their clothes and luggage. As an artist, I consider myself a witness of my time. My work documents the news by criticizing the violence manifested in the displacement of refugees and reflects an engagement, a manifesto against the war”.

Issam Kourbaj was born in Suweida, Syria in 1963. He studied Fine Arts in Damascus, architecture in St. Petersburg, and theater design in London. Since 1990, he has lived and worked in Cambridge, England, and is currently a Lector in Art at Christ’s College. Since the 2011 uprising, he has been making artwork based on the war in Syria, raising awareness and funding for projects and aid. His exhibited work Dark Water, Burning World (2017) is made of repurposed discarded steel bicycle mudguards turned into small boats filled with extinguished matches held by clear resin. Kourbaj numbered each of the boats on the outside, attempting to give a number and recognition to the countless lives perished in the Mediterranean waters. The first edition of this artwork was presented on March 15, 2017, the sixth anniversary of the onset of the civil uprising in Syria in 2011. Since then another edition of his Dark Water, Burning World has been recently acquired by the British Museum. Kourbaj explains his work in the Brooklyn exhibition:

“My Dark Water, Burning World is inspired by ancient Syrian sea vessels and deals with the way present-day Syrians escape while they carry visible and invisible scars scorched into them by separation from their homeland. They have not only lost their land, possessions, homes, and people, but also, for many, their pride and identity. They have lost the tangible and the intangible, their pasts, presents, and most notably their futures. The sea is neither abundant nor beautifully mysterious for many Syrian refugees. It has turned into a terrifying passage through which their fates are being decided: to live or die”.

Muhammad Hafez was born in Damascus, Syria in 1984 and raised in Saudi Arabia. He first came to the U.S. in 2003 as an international student studying architecture. A travel ban kept him from returning to Syria until 2011, the eve of the civil war. Hafez joined the exhibition with two of his art works: Damascene Athan, 7 (2017), made of plaster, paint, and found objects, is part of a twelve-piece series carrying the same title which derives from the daily call to prayer coming from the Great Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, one of the earliest mosques dating to 706. Within an ornate mirror frame a vignette of city life in Damascus is reflected through the protruding ensemble of various small repurposed items made to look like the architectural details of the city. The piece also includes an audio recording captured by the artist during his last visit to the city in 2011. Hafez describes his work as such:

“Damascene Athan emerges from recordings I made during my last visit to Damascus, in 2011, on the eve of the Syrian War. I integrated those final few moments of peace into the decorative mirror frames, which remind me of the plush Victorian interiors we had to leave behind. The daily calls to prayer from the Great Umayyad Mosque of Damascus can be heard in the background, and Islamic calligraphic graffiti decorate the walls. In 2011, although life seemed very peaceful at the time, one could not help but feel a greater danger looming over Damascus, fueled by the Arab Spring momentum and the demonstrations that had already started in southern Syria. The Toyota truck included in the work is a vehicle notoriously used by the Syrian secret service. Having this vehicle parked outside anyone’s house meant bad news. While flowers and jasmine ivy continued to peacefully grow on our architecture, so did the fear and stress represented by the surveillance camera visible in the work.”

In his other work in the exhibition, Baggage Series, 4 (2016) Hafez also uses mixed media (plaster, paint, antique suitcase, found objects) to create a small model of a blown-up multistory building arranged over a suitcase. Hafez explains this piece:

“Baggage Series, 4 alludes to the traumas that refugees carry with them—the toll it takes physically and mentally. Each painstakingly detailed, multi-layered model stretches skyward from suitcases that were themselves donated by the descendants of earlier generations of immigrants to the United States, who fled Europe and the devastation of the Second World War. My juxtaposition of contemporary art and historical artifact physically joins the stories of Syrian refugees to America’s long heritage as a nation of immigrants. In its ability to connect with audiences at the level of their lineage, Baggage Series, 4 transcends a purely humanitarian position and intervenes in the complicated racial and nationalist dimensions of refugee resettlement today”.

In his description Hafez touches upon a critical and current discussion in the U.S. not as a citizen but as a resident who can’t go back to his war-torn country. Although America has generally been called a nation of immigrants, when it comes to new immigration not everyone is welcome. In recent years especially during the administration of President Donald Trump, Muslim, Latino, Non-European, Poor are labels that could define the unwanted or unsuitable immigrant. The first “Muslim ban” implemented by the Trump administration was not long before our exhibition. On January 27, 2017 President Trump signed an executive order that banned foreign nationals from seven predominantly Muslim countries, Chad, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen, from visiting the country for 90 days, suspended entry to the country of all Syrian refugees indefinitely, and prohibited any other refugees from coming into the country for 120 days. After challenges in courts, a new executive order was issued on March 6, 2017. This time those who already had visas and green cards were exempted and Iraq was removed from the banned countries. The third version of the ban, which is still in effect since September 24, 2017, blocks travel to the United States from six predominantly Muslim countries and also includes North Koreans and certain Venezuelan government officials. Nearly every single person from the Muslim-majority countries is barred from getting a green card, no matter what family, business, or other U.S. connections he or she may have. If the Brooklyn Museum exhibition coincided with the first ban or if the artists did not already reside in the U.S. or hold other citizenships during the second ban, their attendance to the exhibit would have been impossible. Although the exhibition was saved from previous Muslim bans or new legal decisions, another seemingly unrelated political event affected our exhibition in a very unexpected way.

Opening Week Events

As we were installing the exhibit, AAEI conducted a press briefing on October 10, 2018 where I, as the curator of the Syria exhibition, was asked to give a brief explanation on the exhibit. I focused on the historical and contemporary parts of the exhibition and its main message. Afterwards one journalist in the audience wanted to talk to me on the Saudi connections of the exhibition since Misk Art Institute was supporting the exhibit. When I tried to explain that our exhibition was curated without any restrictions other than the theme of Arab Arts as part of the Initiative, he was still pushing some hypothetical scenarios that wouldn’t work under the initiative such as an expo on Yemen.[15] Considering none of this was part of an interview which I declined in the first place, the journalist’s push to read more political intrigue showed to me that they were not interested in the exhibition but how it could be used against Saudi politics. That morning I had heard briefly that a Saudi journalist was reported missing since he had entered the Saudi consulate in Istanbul but I did not expect that this could be associated with the initiative or our exhibition during the press launch. Sure enough, as the events developed and the Saudi crown prince’s involvement appeared more and more probable in relation to the disappearance of Jamal Khashoggi, anything even remotely tied to the prince became a target to protest over the killing of the journalist. The AAEI was partially funded by the Misk Art Institute, which also received funding from the crown prince, but to protest the entire initiative based on its partial funding in my mind was very unfortunate. Just like the Syria exhibition, many of the collaborators of AAEI had overlapping interests but these programs had nothing to do with the Saudi world let alone the crown prince. The remaining week only added more pressure from the activists and the public. In the end following the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s decision to decline funding for their scholarly seminar “Collecting and Exhibiting the Middle East”, the Brooklyn Museum announced that it would self-fund the Syria exhibition which had opened on October 13, 2018 and keep it under the AAEI.[16]

The main event of the exhibition “Conversation: Artists on the Refugee Crisis” soon after the opening took place on the evening of October 19, 2018 with the inclusion of three artists and myself. I began with a tour of the exhibition emphasizing Syria’s changing story over time and to the fact that anyone, anywhere, can become a refugee and no geographical location can guarantee immunity. Before the artist presentations, the museum’s decision not to use the funds from the Misk Art Institute for the exhibition was announced and it received an applause from the audience. Although the artists and I were appreciative of the continued support of the museum without the funds from the Misk Art Institute, I also felt that the initiative’s efforts promoting Arab arts and artists from all backgrounds were wrongly targeted in the mix of unfortunate political events. The evening continued with detailed accounts of the three artists and their perspectives on the refugee crisis reflected through their artworks. The engaged audience often responded with tears in their eyes.

Since two of the artists were based in Lebanon and the U.K., only a few activities were planned during their short stay in New York. Ginane Makki Bacho discussed her works in the exhibition with a group of students from the Pratt Institute from which she herself received an MFA degree. Makki Bacho and the students were both very appreciative of this experience. Issam Kourbaj conducted a hands-on workshop where young children created boats made of aluminum foil similar to the ones the artist displayed in the exhibit. When many youngsters successfully created their own refugee boats, Kourbaj asked each of them what they would take if they had only a few choices. While many of them seemed to be far from the world of refugees, their simple answers often gave a stark view of the direness of the situation.

Later during the course of the exhibition, Muhammad Hafez, who is a resident of New Haven, met a large group of students from the Khalil Gibran High school in Brooklyn, named after the famous Lebanese American poet. The school with a large group of Arabic speaking students had a chance to listen to the artist who not only talked to them about his works but further about the fact that such an exhibit was about them as well. Although none of the artists could join, I also gave a tour of the exhibition to a group of students from the Westover school, in Connecticut, where Hafez also worked on an art project.

The relatively short exhibition ended on January 13, 2019 and was visited by over 30,000 people. I believe the unfortunate events around the opening of the exhibit deflected attention from its main message. The Saudi journalist’s horrible killing overshadowed the millions who died in Syria or became refugees struggling to stay alive. If the initiative overall did not receive negative attention related to Saudi funding, both the exhibition and its public programs would have been better promoted and touched more people. I plan to include the story of the Circassian refugees in the display of Raqqa ceramics in the permanent gallery of Arts of the Islamic World at the Brooklyn Museum in order to keep the discussion of past and present refugees alive. Mohamad Hafez’s Damascene Athan, 7 has been gifted to the Brooklyn Museum by the Barjeel Art Foundation in United Arab Emirates after the exhibition and it will help keep this message active especially since Mohamad Hafez’s grandmother was a Circassian who came to Syria as a refugee herself. Those who perished in the Syrian war and those who still struggle to survive in different parts of the world as refugees deserve a lot more recognition and empathy by compassionate humans who happen to live in security. I hope the refugees of the past, the Circassians who came and found a home in Syria, will also be remembered as we look at the display of Raqqa ceramics at the Brooklyn Museum in the future.

References

Bergman, S. M (1974). “Azeez Khayat (1875-1943) A noted Collector of Ancient Glass”. Carnegie Magazine, June: 238-244.

Chatty, D. (2017). Syria: The Making and Unmaking of a Refuge State. London: Hurst & Company.

Jacobs, L. (2015). Strangers in the West: The Syrian Colony of New York City, 1880-1900. New York: Kalimah Press.

Jenkins-Madina, M. (2006). Raqqa revisited: Ceramics of Ayyubid Syria. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Meinecke, M. (1954-2002). “Al Raqqa”. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition. Leiden.

Yoltar-Yıldırım, A. (2013). “Raqqa: The Forgotten Excavation of an Islamic Site in Syria by the Ottoman Imperial Museum in the Early Twentieth Century”. Muqarnas 30: 73-93.

Yoltar-Yıldırım, A. (2006). “The Ottoman Response to Illicit Digging in Raqqa”. In Jenkins-Madina, Raqqa revisited. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art: 218-20.

[1] The Penn exhibition “Cultures in the Crossfire: Stories from Syria and Iraq” ran from 8 April 8, 2018 to November 26, 2018.

[2] These brainstorming sessions for possible future exhibitions were initiated by the chief curator of the Museum at the time, Jennifer Chi.

[3] I am thankful to Kathy Zurek-Doule, Curatorial Assistant in Egyptian, Classical, and Ancient Near Eastern Art, at the Brooklyn Museum for her assistance.

[4] Not all the coalition partners listed here remained by the start of the initiative in October 2018.

[5] Misk Art Institute is an artist-centered cultural organization operating under the auspices of the Misk Foundation, established by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud. Led by Saudi artist, Ahmed Mater, the Institute was established in 2017 to encourage grassroots artistic production in Saudi Arabia, nurture the appreciation of Saudi and Arab art and enable international cultural diplomacy and exchange.

[6] However further connections were not developed for the exhibition.

[7] Photographs taken by the famous British traveler and archaeologist Gertrude Bell when she spent a considerable time in the region show the ruins in Raqqa in detail: http://www.gerty.ncl.ac.uk/search_photos_results.php?search_photos=rakka&Submit=Search+photos

[8] A few examples in the Freer and Sackler: 1908.138 1908.140; In MMA: 48.113.9, 48.113.13, 48.113.14, 48.113.15.

[9] Conservation of the objects was conducted by Lisa Bruno and Harry Debauche.

[10] I am thankful to Harry Debauche who conducted these studies. His results were also made available on the Brooklyn Museum’s tumblr page:

https://brooklynmuseum.tumblr.com/post/178757699919/the-city-of-raqqa-in-modern-syria-was-a-major

[11] David W. Lump, “Record of Mosque Hints at Muslims’ Long History in New York” New York Times, December 9, 2015: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/10/nyregion/mosque-shows-that-muslims-have-long-been-a-part-of-new-york.html

[12] Washington Street Historical Society preserves the memory of the neighborhood: http://savewashingtonstreet.org/photographs-and-artifacts/ Carmen Nigro, “Remembering Manhattan’s Little Syria” November 19, 2015. https://www.nypl.org/blog/2015/11/19/manhattans-little-syria

[13] https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/24/arts/design/arab-art-new-york.html

[14] https://vimeo.com/266504698

[15] James Reinl “Saudi-funded art show in US extols freedom as country cracks down on critics, Middle East Eye, October 10, 2018: https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/saudi-funded-art-show-us-extols-freedom-country-cracks-down-critics

[16] The announcement was published in the New York Times on October 18, 2018: “in light of recent events and in harmony with the international community’s concerns,” the museum will not use Saudi money for its exhibition, “Syria, Then and Now: Stories from Refugees a Century Apart,” which began last Saturday”.

A critical opinion by Rijin Sahakian covering the initiative was published in Hyperallergic on November 1, 2018: https://hyperallergic.com/468850/saudi-arabia-and-us-art-institutions/. A response to it came from Stephen Stapleton, on November 30, 2018 in Hyperallergic: https://hyperallergic.com/473213/a-response-to-how-saudi-arabia-and-us-arts-institutions-partnered-on-a-cultural-diplomacy-offensive/